Originally posted by sonorajim

View Post

If the Chargers have a running back who can do *that*, he'll be making TWO roster spots more effective-- his own, and Ekeler's.

I'm really hoping that Spiller is up to the task, but of course we have no real clue until we see scrimmages and pre-season games.

I think Zander Horvath is another candidate to be the short yardage answer. His best asset seems to be as a receiver out of the backfield, but he has the size, quickness and power to be given a shot as the short yardage specialist.

Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson carries the ball during minicamp in Costa Mesa in June.

Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson carries the ball during minicamp in Costa Mesa in June.

Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson carries the ball during a game for a youth team in Immokalee, Fla.

Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson carries the ball during a game for a youth team in Immokalee, Fla. New England Patriots cornerback J.C. Jackson warms up before a game against the Houston Texans in October. Jackson signed a five-year contract with the Chargers in March.

New England Patriots cornerback J.C. Jackson warms up before a game against the Houston Texans in October. Jackson signed a five-year contract with the Chargers in March. Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson during his playing days at Immokalee High School in Immokalee, Fla.

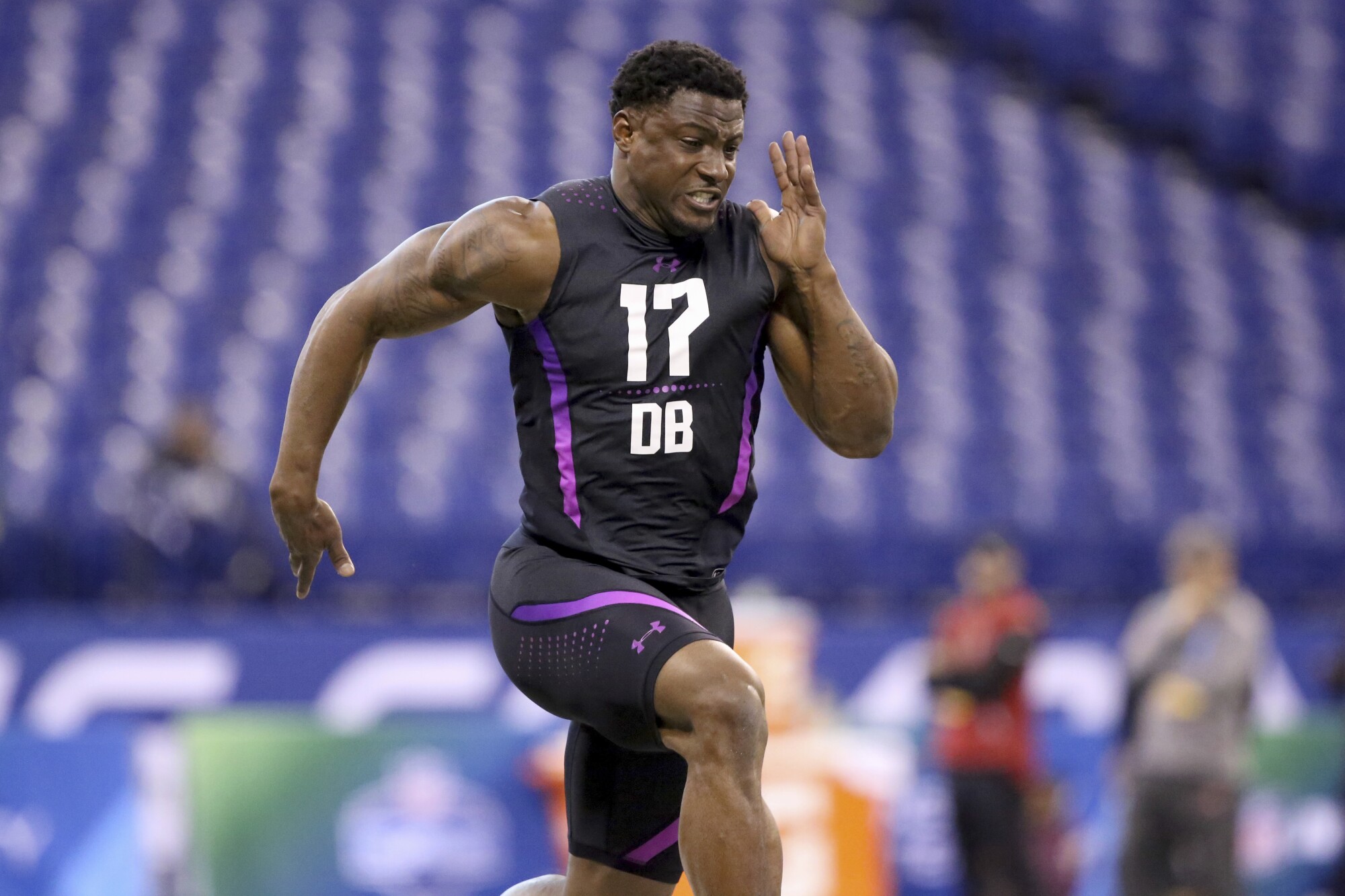

Chargers cornerback J.C. Jackson during his playing days at Immokalee High School in Immokalee, Fla. J.C. Jackson runs the 40-yard dash at the 2018 NFL Scouting Combine.

J.C. Jackson runs the 40-yard dash at the 2018 NFL Scouting Combine.

J.C. Jackson and his mom, Lisa Dasher, and dad, Chris Jackson, stand with their son after he signed with the Chargers in March.

J.C. Jackson and his mom, Lisa Dasher, and dad, Chris Jackson, stand with their son after he signed with the Chargers in March. Chargers linebacker Khalil Mack answers questions during a minicamp news conference in June. Mack, considered one of the NFL’s top-tier pass rushers, was acquired by the Chargers in a trade with the Chicago Bears in March.

Chargers linebacker Khalil Mack answers questions during a minicamp news conference in June. Mack, considered one of the NFL’s top-tier pass rushers, was acquired by the Chargers in a trade with the Chicago Bears in March. Khalil Mack walks off the field after running drills at the Chargers’ practice facility in Costa Mesa on June 1.

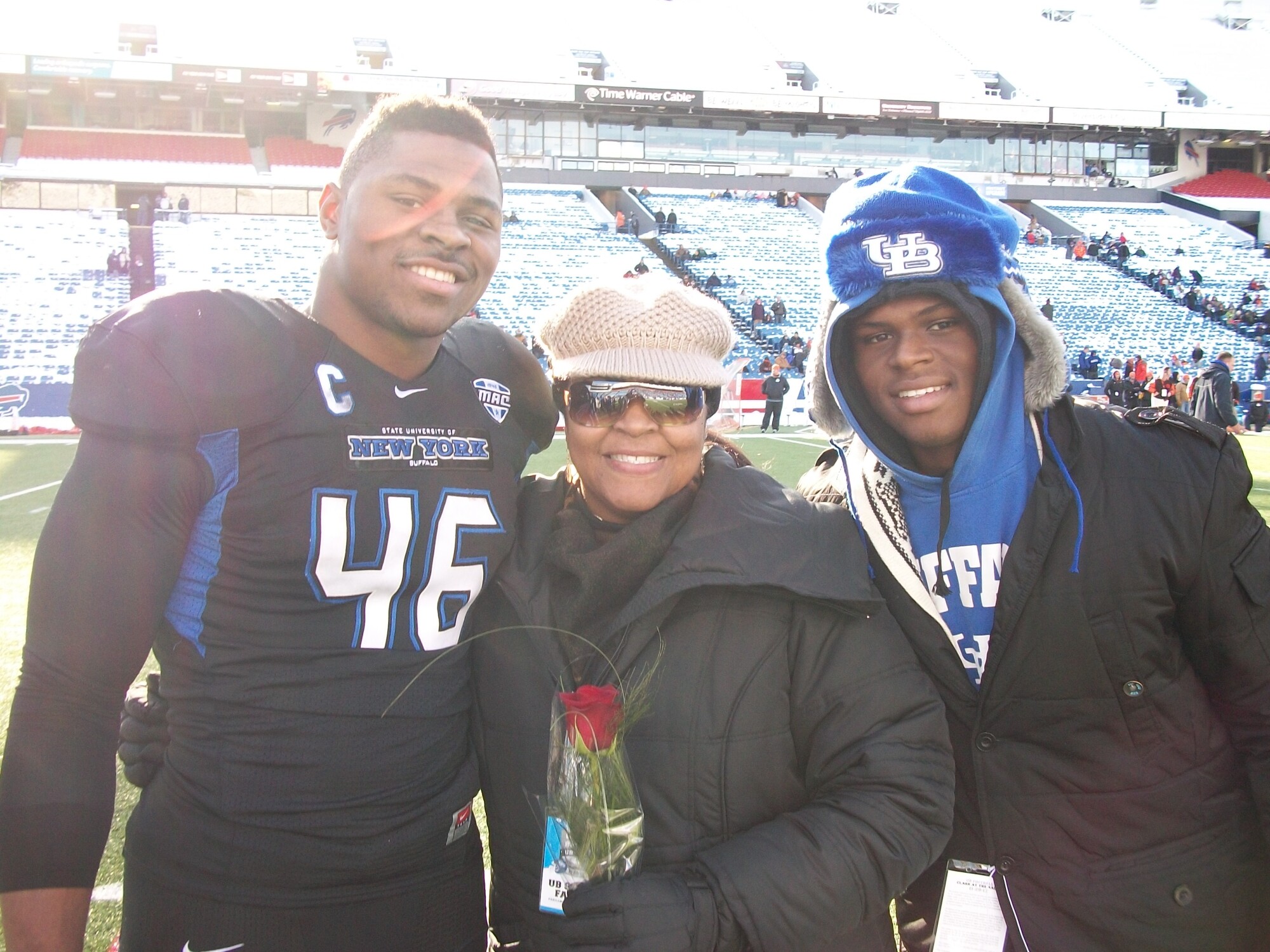

Khalil Mack walks off the field after running drills at the Chargers’ practice facility in Costa Mesa on June 1. Khalil Mack, left, stands next to his mother, Yolanda, and his brother, Ledarius, during his final home game at Buffalo University.

Khalil Mack, left, stands next to his mother, Yolanda, and his brother, Ledarius, during his final home game at Buffalo University. Khalil Mack’s retired jersey at Westwood High in Fort Pierce, Fla.

Khalil Mack’s retired jersey at Westwood High in Fort Pierce, Fla. Khalil Mack walks off the field after a game between Buffalo and Pittsburgh in October 2012.

Khalil Mack walks off the field after a game between Buffalo and Pittsburgh in October 2012. Sandy Mack, left, Yolanda Mack, Khalil Mack and Fort Pierce city manager Nick Mimms at the dedication of Khalil Mack Field in Fort Pierce, Fla.

Sandy Mack, left, Yolanda Mack, Khalil Mack and Fort Pierce city manager Nick Mimms at the dedication of Khalil Mack Field in Fort Pierce, Fla. Khalil Mack attends the 2014 NFL draft in New York with his mother, Yolanda. Mack was selected fifth overall by the Oakland Raiders.

Khalil Mack attends the 2014 NFL draft in New York with his mother, Yolanda. Mack was selected fifth overall by the Oakland Raiders. Chargers linebacker Khalil Mack runs drills at the team’s practice facility in Costa Mesa on June 14.

Chargers linebacker Khalil Mack runs drills at the team’s practice facility in Costa Mesa on June 14.

Comment